I was privileged to be surveyed late last week by the Herald-Leader’s Tom Eblen for today’s column on the state of Lexington’s economy for 2012.

I don’t envy Tom: distilling the often-disparate views of eight different business owners into 800 words or less must be tough. (As regular readers might imagine, my views didn’t exactly align with many of my peers.)

My response alone was over 1000 words, so the understandable – and necessary – result was that some context was stripped from my comments.

Still, Tom asked very thoughtful questions, and I liked some of my answers. So I thought it might be worthwhile to share them here on CivilMechanics.

And if you haven’t read Tom’s column, go check it out here.

(Note: I wrote these answers early Friday morning. Some local events have already outdated at least one answer…)

1. Are you optimistic or pessimistic about the economy this year. Why?

I’m kind of bipolar on the economy. For the first time in 4 years, I’m seeing signs of strength in our business, in our customers and their ability to buy our services, and in the national economy.

At the same time, I see two major “storms” on the horizon: the apparent willingness of Republicans in Congress to scuttle the economy for political advantage (and I don’t think this is a “both sides” thing – see this, for example), and the apparent unwillingness (or inability) of Europe to deal effectively with their debt crisis.

In my view, both storms are fueled by wrong-headed drives for austerity – forcing governments to spend less when no one else is spending, and further drying up demand.

2. How is your business doing? How are business conditions better or worse for you than they were a year ago?

Our business is still weaker than I’d like in the wake of the recession, but it is growing. Sales are up about 3% over last year, but some of the underlying fundamentals still aren’t where they need to be. While we’ve seen some improvement, many of our customers are still delaying basic maintenance on their cars because they can’t afford it.

3. What’s your biggest business concern for the coming year?

I’ve hired two new technicians in the last 9 months, including one last week, bringing us to six mechanics in total. Having more technicians will help us enormously in the busy spring and summer months. But the winter is typically our slowest time of the year, so bringing on an additional employee now is a bit of a risk: Will there be enough work to keep everyone busy and happy? Will there be enough business for me to make a profit while paying them?

Getting through the next few months with a bigger staff is my biggest current concern. Keeping them busy throughout the year by bringing customers through the door is my biggest concern for 2012.

4. What do you see as your biggest opportunity for the year?

Having a larger staff will allow us to serve more customers more quickly. Toward the end of 2011, we were frequently scheduling appointments up to a week in advance because we were too busy to get customers into the shop sooner, and we lost some business because we couldn’t get them in right away. We want to improve our service and accommodate our customers more quickly in 2012, and the additional employees will help us with that.

5. What would you like to see the president and/or Congress do to improve the economy?

I’d like to see another massive stimulus package.

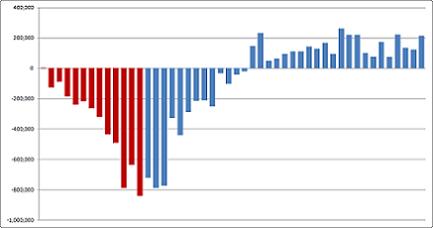

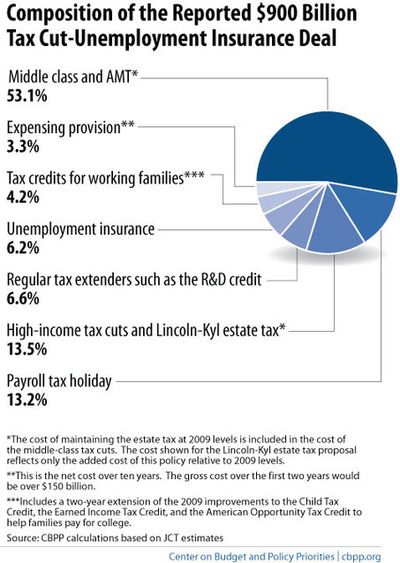

While it may not be popular with your readers, there is no doubt that the early 2009 stimulus worked. (See chart of private-sector job losses and gains at right, stolen from the estimable Steve Benen.) We were losing hundreds of thousands of jobs every month and the economy was imploding. Immediately after the stimulus, the economy stabilized and the jobs losses dropped dramatically, and jobs have been growing slowly and steadily since early 2010. But a stable and slow-growing economy isn’t enough. I’d like to see another stimulus to help jump-start a more dynamic, fast-growing economy.

A lot of folks will say that we need to cut taxes and regulation in order to get the economy growing again. That’s a head-scratcher for me. Lowering my taxes and putting a little extra money in my pocket won’t help me create a job. Neither would letting me pollute more.

I’ve hired two new employees in the last year (growing 25% from 8 employees to 10), and the decision to hire them was driven by customer demand for faster and better service – which had nothing to do with my taxes or regulations. Customer demand drives hiring; giving business owners extra money or convenience really doesn’t.

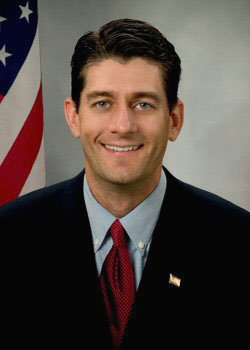

I like President Obama’s American Jobs Act as a starting point for a stimulus – investment in infrastructure, schools, and public safety is a sound way to grow economic demand. But I’d like to see even more investment in other areas, such as energy research and American manufacturing, and I’d like to see a stimulus closer to $1 trillion to really get the economy growing again.

That’s what I’d like to see. I see zero chance of this actually happening with this Congress.

6. Will this year’s presidential election make the economy better or worse? Why?

I fear that it will make things worse, at least for the short term. It is hard to imagine how our political system could be more gridlocked than it was in 2011. Still, as congressional Republicans obstruct any initiative which might make the President look good, I worry that they’ll sacrifice the economy on the altar of politics.

As for the race itself, I see a worrying thread of extremism from the GOP candidates. Even the supposedly-moderate Mitt Romney is proposing extreme policies which benefit the wealthy even more and skewer the middle class and poor even more (thereby skewering most of my customers). I worry that the austere policies a Republican President might attempt to implement would decimate my customer base and my business.

7. What is Lexington’s biggest asset during these economic times? It’s biggest problem?

I think our schools – particularly UK – are our biggest asset. They provide our city with well-educated people, great research to improve our lives and build businesses upon, and a vibrant “student economy” which spills over into the rest of our city.

I see two big problems for Lexington. First, if the proposed redistricting is approved by Governor Beshear, a huge chunk of our city will not be represented in the Kentucky State Senate for two years. Proper representation in Frankfort is vital to protecting Lexington’s interests and to protecting UK, and these undemocratic redistricting plans would deprive one-third of our city of its vote. I worry about the impacts of Lexington not being represented in Frankfort.

Second, I think our city, our state, and our schools are under-funded. I appreciate all of the efforts Mayor Gray has made to trim Lexington’s budget, but at some point, we citizens need to fund all of the services and infrastructure and improvements we’ve come to expect.

I want nice roads for me, my customers, and my employees. I want them to be plowed and salted when nasty weather strikes this winter. I want the best schools for my son and for my employees’ families. I want the best fire and police protection. I want a beautiful and safe city to live and work in. But those benefits come at a price. And we’re responsible for funding all of those “nice things”.

It won’t be popular, but I think we need to start a frank conversation about raising taxes to fund our city’s (and state’s and schools’) obligations. We need to pay for the great things we want to do together.

8. What else should readers know that I haven’t asked about?

I hope they’ll go out of their way to buy local goods and services when possible. That will keep more of Lexington’s money in Lexington, which helps foster a more vibrant local economy.