Imagine, for a moment, that you build houses.

You’re a competent – and pretty crafty – builder, so you earn a profit of 10% of the sales price on each house you build.

You’ve found a cheap lot on the edge of town which is a decent prospect for a $125,000 home design. At your 10% margins, you’d usually stand to make $12,500 on this house.

Trouble is, your land is in the middle of nowhere: the nearest street dead-ends before it even reaches your lot. You know that paying to extend the street will cut into your profits by $5,000, and you definitely don’t like that.

As you’re thinking really hard about how to avoid having to pay for the street extension, you hit upon a really crazy scheme: What if, you think to yourself, I could not only get our town to pay for the street extention, but I also got them to finance the house’s two-car garage!

But how could you possibly convince the townsfolk to fork over the $25,000 needed for the street extension and the garage? The town is already struggling with its finances, and you know your proposal won’t go over well. Why should the town pay for a private garage?

And here is where you get your craftiest.

You decide to focus more on what the town gets than on what they spend. So you play up ‘benefits’ the town stands to gain from your ‘economic development initiative’. Here’s your basic approach:

- Building the house will generate higher property taxes for the town over the next few decades, where today there is just a vacant lot.

- The construction will increase economic activity for the town as you pay for supplies and labor on the site.

- The house will bring in working residents, who will generate new payroll taxes for the town.

- The garage and street extension – ‘public infrastructure’, as you now call the garage and road that you need more than anyone – are essential to this future tax revenue. You’ll point out that no one will buy a new house without a garage; and without the garage, the town won’t get the benefits of this project.

- Yes, the town would have to borrow the $25,000 (and, over the years, pay another $25,000 in interest) to help fund the ‘infrastructure’, but you’ll point out that the new property and payroll taxes will offset those costs.

- Finally, to sweeten the pot, you artificially inflate the price of your house by 20% to $150,000. You know the project is really only worth $125,000, but boosting the price by 20% has the nifty effect of inflating the estimated ‘benefits’ by 20%, which makes the whole scheme easier to sell.

You know you are way out on a limb with this scheme, but – who knows – maybe the town will go for it.

And why would they? Because you’ve done the math, and you’re betting that they haven’t.

If you had paid for the street extension on your $125,000 house, you would have spent $117,500 and pocketed $7,500 – a tidy 6% profit. Not what you usually make, but a profit nonetheless.

But if you can get the town to finance the street and the garage, that removes $25,000 from your cost. Now, you can build the $125,000 house for just $92,500 out of your pocket (and another $25,000 out of the public purse), and you make a cool $32,500 profit for a 26% margin.

If you can get the town to go for your scheme, you’ve ‘magically’ quadrupled your profits.

::

So you package up your scheme and present it to the town’s economic development manager. You brace for her to laugh you out of her office, but have decided that you can live with a little ridicule in exchange for the chance – however remote – to quadruple your income.

Instead, she just smirks.

She knows that you need the garage and the street extension more than anyone, and isn’t sure what valid public interest the town has in helping with the house you want to build. She know that you need to build something on the lot anyway even if you don’t get the town’s financial support. She’s not sure she believes that your project is really worth the $150,000 you are claiming. Even if it is worth $150,000, she thinks your estimates on how much the town stands to benefit are extremely exaggerated.

She appreciates the ingenuity of your argument, but the whole scheme strikes her as farcical and not really worthy of being called an ‘economic development initiative’.

And yet, she also knows that you are close to several members of the town council. She seems to recall a picture of you with your arm around the mayor in the local paper. She suspects that you have contributed to several local political campaigns.

These connections intimidate her. So she decides to pass the whole suspect bundle (and the decisionmaking) along to the town council.

And to your delight, the council routinely passes your scheme with only modest resistance. They simply require that you spend at least $100,000 on your project to qualify for these incentives.

::

Just as you rub your hands in glee at the prospect of making so much money, the economy takes a nosedive. Banks aren’t willing to lend for housing construction, even for a ‘sure thing’ like your project.

After a long delay in lining up financing, you return to the town council with a proposed amendment to your initiative. You ask for a ‘hardship exemption’ to lower the total amount which needs to be spent on the project to just $75,000, even though you initially justified the town’s financial involvement based on the inflated $150,000 amount.

You hope that no one notices that a half-sized project would only generate half-sized benefits.

And, sure enough, the town council unanimously approves your amendment without debate. No one noticed. Or, more accurately, no one publicly objected.

At this point, another important revelation strikes you: The smaller your project gets, the more you come out ahead.

You now figure that you can finance and build an $80,000 house on your lot.

If you had built on your own, the house would have cost you $72,000 to build, plus $5,000 for the street improvments, which would have left you with about $3,000 in profit. At just under 4%, the margins are substantially less than you usually make, but the project is still profitable.

But the town is still on the hook for the same garage and street extension – even though the overall house has shrunk. So you’ll really spend $52,000 to build your $80,000 house (while the town still pays $25,000), and you’ll clear a neat $28,000, or over 9 times as much as if you built the project on your own.

The town’s ‘public infrastructure’ commitment lets you multiply your profit as the overall project shrinks. You put in less money and get higher return on investment.

You are quite crafty, indeed.

::

Yes, this thought experiment is ludicrous, if intriguing. And no town would ever support such a ludicrous scheme.

Right?

Except that they already have.

The above fable is true. Mostly.

It’s just 2,000 times too small.

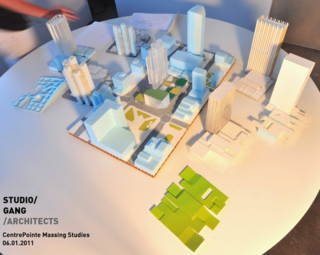

Multiply all of the dollar amounts by 2,000, and you have the fiscal outlines of the CentrePointe project in Lexington.

Just substitute ‘town’ with ‘The Commonwealth of Kentucky’ and ‘Lexington’. Then substitute ‘you’ with ‘The Webb Companies’. Substitute ‘house’ with ‘CentrePointe’. And substitute ‘incentive’ with ‘Tax Increment Financing’ or ‘TIF’.

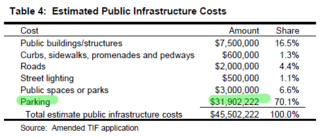

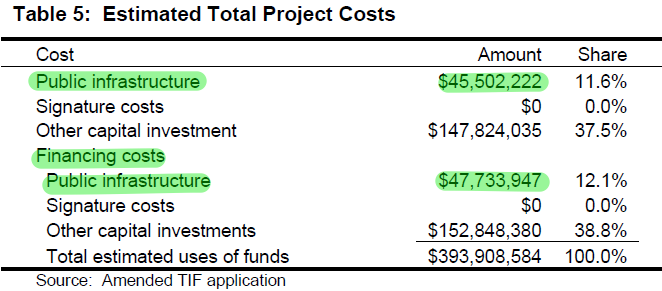

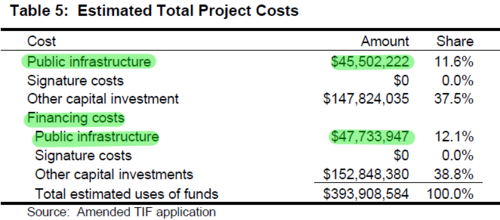

CentrePointe started as a $250 million project in 2008. As it sought state and local support for $50 million in ‘public infrastructure’ (including a $30 million parking garage), CentrePointe’s cost ballooned to $300 million. After getting approval for Tax Increment Financing incentives from the state – based on that $300 million price tag – CentrePointe still couldn’t get financing, and stagnated.

After continual financing troubles and multiple revisions, last week CentrePointe’s developers got unanimous approval from both houses of the state legislature to drop the overall project size to just $160 million – while still receiving the full TIF incentives of the inflated $300 million version of the project.

In other words, no one noticed that a half-sized project only generates half-sized benefits to the state and city. No one recalibrated the incentives when CentrePointe shrank.

In the process, The Webb Companies multiply CentrePointe’s profitability with no additional risk to themselves.

::

We’ve often called Tax Increment Financing (or TIF) a scam or a con. While this sounds like hyperbolic exaggeration, we think what’s actually happening is sleazy enough to merit these labels.

TIF’s scamminess stems from several interrelated components:

First and foremost, the developers shouldn’t need public help. They benefit from this ‘public infrastructure’ more than anyone else, but have no financial stake in it. The theory of TIF is that the taxes stemming from new economic activity will pay for the infrastructure. In return, the city gets the benefits of increased economic activity. That’s the theory.

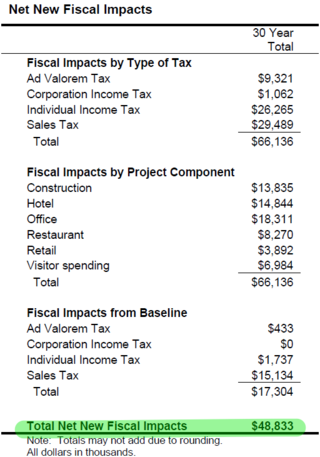

But the reality is quite different. The most aggressive, best-case scenario from the state’s economic development consultant showed the city and state tax increments not quite breaking even after 30 years.

All of the incremental benefits that the project is supposed to bring are plowed right back into debt and interest payments which benefit the developers.

So in return for taking on $50 million in debt and $50 million in interest on behalf of the developers, the public gets nothing after 30 years. Nothing.

And that was the best case?

Wait. It gets worse. The consultant’s ‘not quite breaking even’ case was based on CentrePointe at its bloated $300 million apex. Now, CentrePointe is a half-sized $160 million project. At this reduced size, CentrePointe can never pay the city and state back for the infrastructure investment.

The developers need the parking garage. The developers would benefit most from the parking garage. Even so, the developers have managed to offload their parking garage costs onto others, using public taxes to do so.

Second, this means that TIF allows The Webb Companies to socialize the many risks of CentrePointe while privatizing the gains. Bondholders and the public take on the risks that CentrePointe might fail to live up to the promised (and unlikely) stream of tax revenues, while the developers avoid (and pocket) the costs of a $30 million parking garage. The developers get the benefits of a parking garage to serve CentrePointe, while someone else gets stuck with the tab.

Will bondholders or the public ever get paid back? Maybe. Maybe not. We’re pretty sure that they won’t. In any case, none of this is the developers’ concern. They get a big parking garage – essentially for free.

From a developer’s point of view, TIF offers all upside with no downside.

Third, this asymmetry in risk rewards the developer for, in essence, making stuff up. In order to win the profit-multiplying $30 million upside of TIF approval, the developers can (and did) say anything. “We’re building the state’s tallest building!” “We’ve got all-cash financing!” “We’re building a $300 million development!” “We’ve got handshake deals for 65 condominiums!” “Construction starts in 60 to 90 days!”

The fact that all of those statements were false is beside the point. There was little downside to lying or being profoundly wrong. And the developers were repeatedly, incredibly, and thoroughly wrong.

With no downside, their multi-dimensional wrongness helped the developers secure a $30 million windfall at public expense.

Fourth, as the nature of CentrePointe shrank and changed, the TIF funding stayed the same.

CentrePointe’s TIF was approved when the developers were proposing a $300 million project. At that time, the developers also promised that they had financing in-hand. They promised 91 residential condominiums at a $1 million average price. They promised to begin construction in March 2009.

None of these overly optimistic assertions turned out to be remotely true. The project shrank to half its approved size. The size and mix of residential, retail, hotel, and office activity changed dramatically. The project slipped 4 years (and counting) past its promised construction start date. But none of these facts changed the city’s or state’s TIF obligations.

CentrePointe is a fundamentally smaller and different project than when it was proposed. Yet the developers’ rewards remain the same: The developers still get a $30 million parking garage, at public expense.

There appear to be no mechanisms at the state or local level to revisit the TIF commitments when a project fails to live up to its rosy projections. And CentrePointe certainly failed to meet those projections.

Worse, TIF actually rewards the developers for shrinking the size of the project: The smaller the project gets, the greater the developers’ return on investment.

The Webb Companies appear to be able to alter the project on every whim of the developers. They can and have overpromised and underdelivered. And the city and state appear to have no recourse – or desire – to reevaluate their support of the project.

Fifth, state law is maddeningly unclear about what happens if a TIF project fails to deliver on its promises. The law goes into great detail about how to subsidize the developers, but it does not make clear who pays when the project falls short of projections.

When a TIF project is approved, it allows the city and state to take on debt by issuing special TIF bonds. In return for $50 million from bond investors, the city and state promise to use a steady stream of taxes coming out of the new economic activity at CentrePointe to pay back the $50 million (with another $50 million in interest) over the next 30 years.

Under the original best-case assumptions from the state’s economic development consultant in 2009, taxes from CentrePointe just missed fully paying for the bond payments.

Since 2009, however, everything changed. The project got much, much smaller. Key assumptions justifying TIF for CentrePointe have crumbled.

In other words, it is not remotely possible for CentrePointe to generate enough taxes to pay back the bond investors.

Three years ago, we re-ran the consultant’s analysis for CentrePointe using (in our judgment) generous-but-realistic assumptions. The result: Taxes from CentrePointe only generated 20% of what was needed to pay bond investors.

And that was before the project shrank another $40 million – rendering even our dreary projections too optimistic.

So the state and city issue TIF bonds. And the CentrePointe TIF can never pay the bond investors. Then what?

If the city and state default (i.e., fail to pay) on the bonds, whose credit rating takes a hit? Who is responsible for the shortfall?

Some analysts assert that bondholders would be on the hook for any shortfall. But then, any bond analyst looking at CentrePointe would recognize that they’d never get paid, and investors would flee. Then where do the TIF funds come from?

It is hard to look at the CentrePointe TIF without realizing that there is great risk of loss to state and local taxpayers, as well as bond investors.

It is also hard to look at the CentrePointe TIF without realizing that The Webb Companies incur no risk at all.

Finally, the fact that the city and state sanction TIF for CentrePointe doesn’t make TIF more legitimate; It makes TIF more despicable.

TIF is the worst kind of reverse-Robin-Hood welfare scheme for developers. At a time when the state and city are starving for money, TIF uses public tax dollars to help reduce the developers’ expenses and helps line their pockets. It transfers risk away from the developers and to the public and to investors. It literally takes from the poor and gives to the rich.

The CentrePointe TIF is a con. The fact that the city and state assist in the con doesn’t make it any less of one.

::

We’ve often had fun at the developer’s expense with CentrePointe, pointing out their serial incompetence and their tendency to lie and exaggerate.

But the truth is that their ‘incompetence’ and mendacity have served them quite well. It has helped them dramatically compound their profitability and reduce their risk. All at public expense.

Quite crafty, indeed.