Call it “CentrePointe Fatigue”.

After six-and-a-half years of bulldozing, promises, broken promises, half-truths, and outright lies on the CentrePointe project, folks are just plain tired of talking and thinking about CentrePointe. They’re tired of waiting. They just want something, anything to be built on the long-empty block in the center of our city.

And I get it. After writing over twenty posts examining the business model, architecture, and politics of CentrePointe (see here and here for a sampling), I got tired of talking and thinking about it, too. The interest and outrage was hard to sustain (even if thoroughly justified).

You can see it in online conversations. You can see it in the newspaper1. You can see it in Urban County Council meetings. The coverage and the questions got lazier. At some point, the fatigue just took over. People lost the will to keep investigating and to keep fighting, especially as the project stalled repeatedly.

And that’s precisely what the developers have counted on all along.

If they just waited us out and wore us down, they could walk off with their bonanza payout financed with our tax dollars, and we’d all be too tired, too exasperated, or too relieved to notice.

Against this backdrop of CentrePointe Fatigue, Lexington’s Urban County Council voted 15-0 last Tuesday to approve a new scheme to finance a $32 million parking garage for CentrePointe.

But what really happened was deeply disturbing: The Council unanimously approved a scheme which is designed to defraud investors for the benefit of the developers.

Is ‘fraud’ too strong a term?

Let’s dig in and find out.

::

With any economic development initiative, governments hope to foster increased economic activity in a particular place. The increase in activity is sometimes called an ‘increment’. Tax Increment Financing (TIF) is an economic development scheme where the projected future taxes generated by the new economic activity – the increment – are used to pay for ‘public’ infrastructure improvements.

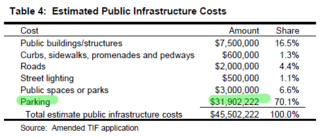

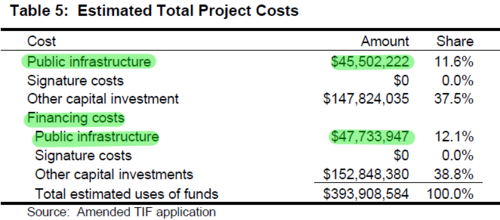

In CentrePointe’s case, these ‘public’ improvements included a $31.9 million underground parking garage, as well as improvements to sidewalks, sewers, streets, and the rapidly-deteriorating Old Courthouse. In all, CentrePointe includes about $45.5 million in so-called2 public infrastructure.

The CentrePointe TIF proposed financing the infrastructure by issuing bonds to investors, and paying those investors back – plus interest – over the next 30 years with the ‘tax increment’ generated from the project.

Would CentrePointe be able to generate enough in new taxes to pay bond investors?

That was the central question of a 2013 report [PDF download] commissioned by the Cabinet for Economic Development and written by AECOM Economics, a Los Angeles based consultancy.

The AECOM report stands as the only comprehensive evaluation of the economic impacts of CentrePointe in its current incarnation.

AECOM’s report is deeply flawed3. It uses non-standard valuation techniques which tend to dramatically overstate how much CentrePointe is worth to the community.

Despite its flaws, AECOM’s evaluation is still instructive: it raises significant doubts about the viability of the CentrePointe TIF. It also contains what state and local officials knew (or should have known) about whether the TIF could be successful.

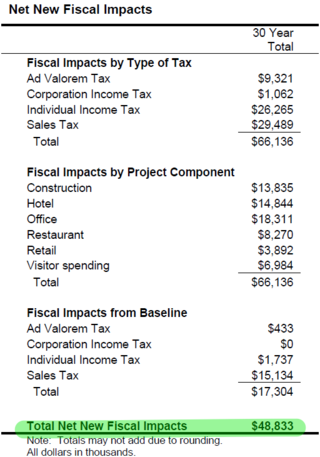

There are two key tables in the 52-page report which should have set off alarm bells for the Cabinet for Economic Development and for the Urban County Council.

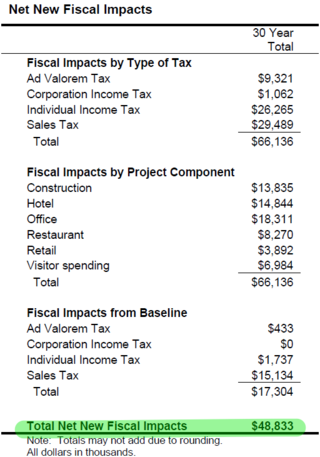

In the opening pages of the report, AECOM sizes CentrePointe’s tax increment: $48.8 million. Compared to what was there before, AECOM claimed that CentrePointe would be expected to generate nearly $49 million in new taxes over the next 30 years.

CentrePointe Tax Increment: $48.8 million (AECOM Report, June 2013, p.3)

So, would that be enough to pay back bond investors?

No.

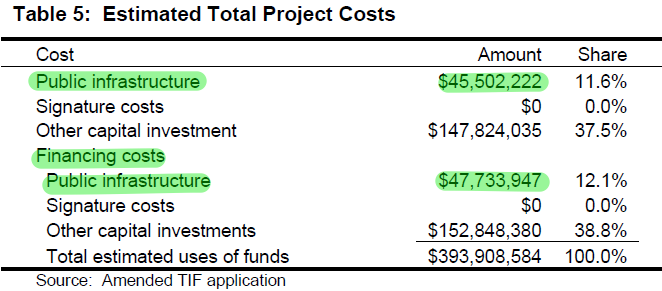

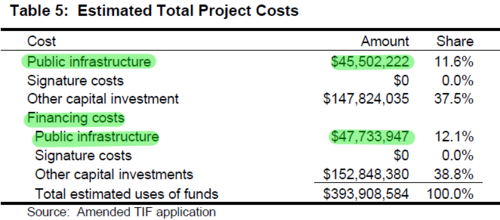

A little deeper in the report, AECOM summarizes the public costs of the CentrePointe infrastructure bonds. While the ‘public’ infrastructure would cost $45.5 million, the interest payments (called ‘financing costs’ in AECOM’s report) on the infrastructure bonds would pile up another $47.7 million. Over the next 30 years, then, the infrastructure bonds would cost a little more than $93 million.

CentrePointe Bond Cost: $93.2 million (AECOM Report, June 2013, p.10)

How can $49 million in new taxes from CentrePointe pay off $93 million in debt and interest for the infrastructure bonds?

It can’t.

And therein lies the central fraud of the CentrePointe TIF. There will never be enough economic activity on the CentrePointe site to pay off the debt and interest on the infrastructure. That’s what the only credible, comprehensive analysis of CentrePointe says.

The Cabinet for Economic Development should have known this. (It was their report.) The Urban County Council should have known this. (They were provided the AECOM report before approving the CentrePointe TIF).

Despite knowing that the CentrePointe TIF could never pay for itself, in July 2013 both the city and state approved this audacious scheme to offer fraudulent bonds to investors which they knew could never pay what was promised.

And they approved this scheme all for the benefit of the developers, who get a ‘free’, taxpayer-financed parking garage.

Pretty bad, huh?

Wait, it gets worse.

::

For the CentrePointe TIF, the state will set aside the new, incremental taxes generated by CentrePointe, in order to repay the public infrastructure bonds. The state will hold on to those taxes until at least $150 million in capital is spent on the CentrePointe site. (This is a requirement of Kentucky’s ‘Signature TIF’ law.)

Once the state and city approved the CentrePointe TIF scheme, the developers began to dig and blast for the development’s $31.9 million underground parking garage.

After the developers completed most of the digging last month, they returned to the city and the state with an even more audacious scheme. They asked the city and the state to issue bonds for the parking garage now – before they had spent anywhere close to the $150 million required to release the incremental taxes for repaying the bonds.

The state Cabinet for Economic Development refused the request, and claimed that it was more appropriate for the city to issue the parking garage bonds.

The Urban County Council debated the request, with many council members (appropriately) expressing reservations about the liability for the city in issuing bonds before anything was built which would generate the funds to repay them.

Last Tuesday, the Council heard – and approved – an even more convoluted proposal. (This GTV3 video captures the entire 40-minute meeting.)

The Kentucky League of Cities (KLC) – a non-profit association of Kentucky’s cities – offered to act as a conduit to issue the parking garage bonds under its authority. In order to do so, Lexington would need to enter into an interlocal agreement with another Kentucky city (in this case, Midway) to form a new non-profit corporation which would issue the new bonds. Lexington would pledge its portion of the TIF revenues to KLC for the repayment of the bonds.

While there were a few pointed questions from council members about the project, the overall mood in the room seemed to be a palpable sense of relief – something, anything was finally happening. There was also palpable relief that this whole issue would soon be someone else’s liability.

The council voted 15-0 to pursue using KLC to issue the parking garage bonds. Most of the participants congratulated one another on the ingenuity of this new scheme.

They shouldn’t have. Their hands are far from clean.

By inserting additional layers into the already-labyrinthine CentrePointe TIF scheme, the Urban County Council unanimously voted to make it nearly impossible for bond investors to understand that they will never get their money back.

During last Tuesday’s Council meeting, Roger Peterman – a partner at Dinsmore and Shohl who consults with the city on bond issues – claimed that the potential bond investors “are sophisticated investors [who are] willing to analyze more difficult credits like these.”

Let’s parse that a little. As a so-called ‘sophisticated investor’ myself4, I wondered about how other sophisticated investors would get access to information on the CentrePointe TIF.

When I contacted the Cabinet for Economic Development to obtain a copy of the AECOM report, for instance, I was told “The consultant’s study is protected from public disclosure by state law.” Remember, this is the only credible report on the CentrePointe TIF, and the public agency which commissioned the report was refusing to release it to the public.

I managed to obtain the report through other channels, but I wonder whether the average bond investor would have had the ability and the network to discover it.

Most of these bond investors would deal directly with KLC’s proposed “Lexington-Midway interlocal non-profit bond-issuing shell corporation”5. Very few would have visibility into the convoluted TIF program, much less the precise financial details of the CentrePointe TIF. Even if they knew to look for the AECOM report, how many would press further after being stonewalled by the Cabinet for Economic Development?

‘Sophisticated investors’ also bought the AAA-rated bundles of mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations which supercharged the subprime mortgage crisis in 2008. Calling them ‘sophisticated’ doesn’t mean that they have a clue about what they are investing in.

But the Urban County Council does know what they are doing: They are using KLC to issue bonds which they know can never be paid back. They are assisting in perpetuating the CentrePointe TIF fraud6.

Wait, it gets even worse.

::

Because the state will hold the incremental taxes from CentrePointe until $150 million is invested in the site, that means that there will be no funds available to pay back bond investors until the project reaches that $150 million threshhold.

But if KLC issues the parking garage bonds through their shell corporation today – when only $5 million of capital has been invested – how will bond investors be paid?

What assurances do bond investors have that anything else will be spent, and that the parking garage bonds will ever begin to be paid back? Only the blithe assurances of the developers. And six-and-a-half years later, those assurances carry very, very little weight.

If the project stalls after the parking garage is built, then what?

Wait, it gets even worse still.

::

There’s one more aspect of what the Urban County Council did last Tuesday which should alarm us: They prioritized the CentrePointe parking garage over the stuff that’s truly public: sidewalks, streets, sewers, and the Old Courthouse.

Remember how the CentrePointe TIF application filed by the developers called for $45.5 million in ‘public infrastructure’, including the $31.9 parking garage?

What was approved on Tuesday was a scheme to fund the parking garage alone.

What happened to the other $13.6 million of infrastructure? When and how will bonds be issued for that? Will those bonds be prioritized behind (i.e., paid after) the parking garage bonds?

It was disturbing to see how eager the Urban County Council was to set up financing for the stuff which benefits the developers (the parking garage) without advancing the stuff which is truly public in nature.

::

If the KLC scheme for the CentrePointe TIF proceeds, the net effect of all of these maneuvers is that only one party involved with the CentrePointe TIF comes out ahead: The Webb Companies.

Bond investors are likely to lose about half of their investment – and that’s if the project is ever completed as planned.

Lexington and Kentucky taxpayers will have earned the right to have their future taxes skimmed for the next 30 years to pay back part of the obligations to those duped bond investors, while incurring the additional legal liability for our city officials and KLC having set up a fraudulent bond offering.

The Webb Companies, however, come out way ahead.

By waiting until the public no longer noticed, The Webb Companies get a ‘free’ parking garage financed with our future tax dollars, while incurring none of its associated costs or risks.

If the rest of the project can never be built – and bondholders can never be paid – The Webb Companies still got a brand new underground parking garage (which they never paid for) on their land.

If they do happen to complete the project, their development will be much more attractive to tenants because of the taxpayer-financed parking garage.

The Webb Companies come out ahead whether the development gets built or not.

In the process of using this taxpayer-funded scheme, the Webb’s have likely more than doubled their profits at our expense7.

::

By taking advantage of CentrePointe Fatigue, the developers have once again privatized gains while socializing their risks to the rest of us – as they have done repeatedly over the past 40 years.

Along the way, they have convinced city and state leaders to use our good names (and credit ratings) to defraud bond investors in order to benefit The Webb Companies.

After six-and-a-half years, I know that it is hard to sustain outrage and interest in CentrePointe. But it has never been more critical to be outraged at shameless hucksters who line their pockets with our money.

:: NOTES ::

Read more