(Part of the To-Do List for Lexington series. Click here for an overview and links to the rest of the series.)

Lexington is losing its minds.

At 100,000 strong, Lexington’s college graduates represent approximately one-third of the population over 25 [Source: US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2006 and 2008].

The University of Kentucky and Transylvania University churn out over 6,000 new graduates – including over 4,000 new bachelor’s degrees – each year. With 4,000 new degree-holders per year, Lexington should have increased this talent pool from 100,000 in 2005 to about 112,000 in 2008.

But we didn’t.

Instead, even as Lexington’s overall adult population grew by 9,000 in that 2005 to 2008 period, the number of college graduates remained stuck at 100,000. (For comparison purposes, Louisville grew from 191,000 college graduates in 2005 to 202,000 in 2008 – growth of 5.7%).

Somehow, 12,000 graduates have slipped from our economy – far more than can be explained through normal attrition (retirement, death, etc.).

The explanation: Educated talent is leaving Lexington. We suffer from a “brain drain”.

::

In recent years, it has become fashionable for Lexington’s leaders to talk about attracting the “creative class” to Lexington. Coined by Richard Florida, “creative class” refers to professionals who work in knowledge-intensive industries, and Florida’s theory is that this group of professionals drives economic development in “creative cities”.

When our leaders talk of the creative class, they frequently focus on diversionary amenities which will attract young creatives to our city – entertainment, events, and facilities which will make life in Lexington more enjoyable outside of work.

While not entirely misguided, the problem with this approach is threefold:

- It confuses cause and effect. Is this creative environment really the driver of economic prosperity in American cities? Or, more likely, are they the result – the pleasant side-effect – of a prospering economy?

- The flagrant boosterism which permeates Lexington’s attempt to attract new talent often comes at the direct expense of retaining the talent we already have, as Steve Austin ably points out.

- It assumes that the creative class is something ‘out there’. Lexington already has a creative class. And we must cultivate it here first.

Instead of focusing on amenities, Lexington should focus on crafting a vibrant economic engine which will keep the educated talent our city produces and which will create real demand for those amenities.

::

Who’s leaving?

When we see that Lexington has lost 12,000 college graduates in 3 years, our impulse is to look for an exodus of newly-minted degree-holders, and to start thinking about what we could do to retain our newest, youngest graduates.

And while the loss of a departing new graduate’s energy, potential, and future is certainly tragic, there is an even-more-profound tragedy which Lexington must actively address: the loss of the experienced employee.

When experienced employees with college degrees leave Lexington, they injure our economic engine far more than a young graduate. Experienced employees represent significant investments in training, dollars, relationships, know-how, and, well, experience.

In aggregate, these experienced employees are vast pools of expertise which create enormous economic advantage for Lexington. They have more income than recent graduates. They provide more tax revenue. They have higher property values. They spend more money in the local economy, which creates more local jobs. They tend to add more value to their companies.

This is the primary reason I have been so publicly critical of Lexmark’s implosion. Every few quarters, Lexmark announces fresh rounds of layoffs and “restructuring” which shed dozens or hundreds of local employees. Many other employees have left of their own accord.

Seeking employment which can utilize their expertise, these folks often leave Lexington. Many who remain in Lexington are underemployed. When so many highly-trained experts in engineering, software development, logistics, and marketing leave our city, it is an enormous hit to the local economy.

Lexington must find ways to solve this exodus of talent (in both new graduates and experienced employees). We need to be creative in how we grow, keep, and attract smart people.

Lexington must leverage its intellectual capital.

::

How do we grow, keep and attract smart people? We need to start by helping to create new local jobs.

There is a common misconception that all job growth in the US comes from small businesses. But business size isn’t the determining factor; business age is. The Kauffman Foundation found that all job growth in our country comes from young businesses (regardless of their size). Entrepreneurial ventures founded in the last 5 years drove all job growth in our nation’s economy.

When we think about entrepreneurship, our focus is often (again) on our younger generations. We are drawn to stories of Gates, Jobs, Dell, and Zuckerberg launching wildly-successful ventures from their dorm rooms or garages. They came so far from such modest beginnings. In Lexington, we see this youthful energy and creativity exhibited in Awesome, Inc. (who are awesome, by the way), a local business incubator.

They make really compelling stories. But the meteoric rises of Microsoft, Apple, Dell, and Facebook are so compelling precisely because they are so rare.

And they misrepresent the realities of the entrepreneurial world.

In another counterintuitive study, the Kauffman Foundation found that older, more experienced workers actually start new businesses at higher rates. Other studies have found that the vast majority of technology startups are founded by people 35 or older. And where do many of those older entrepreneurs come from? Often, from large corporations.

So how do we create new jobs in Lexington? How do we keep and attract members of the “creative class”? How do we stem the bleeding of expert talent from our city? Here’s a starting list for leveraging our intellectual capital. I hope you will add to it:

1. Fuel the entrepreneurial engine. From experience, I can tell you that starting a business is daunting hard work. There is the bewildering array of legal and tax implications. There are a variety of financial hurdles. And, unless you’ve done this sort of thing before, there is a ton of on-the-job learning about what you don’t know about starting a business.

Lexington (LFUCG and Commerce Lexington) should strive to streamline the start-up process far more than they do today. Our city should embrace entrepreneurs as they seek to create new jobs for our economy.

We should help them flatten the usual barriers to getting a business started. We should provide forums for getting enrepreneurs connected with other talents and businesses which can assist them in the setup and growth of their businesses. We should give them open access to critical business data about our city. We should give them some amount of preference in local bidding contracts. We should provide them with essential training in operating their businesses (e.g., If they are brilliant engineers, that doesn’t always mean that they are brilliant marketers or financial analysts).

When possible, we could even provide them with financial support or space (such as setting them up in the plentiful space available in Lexington’s Distillery District).

In short, Lexington needs to foster the conditions under which entrepreneurs can create jobs.

2. Grow our pools of expertise. Our mayor frequently talks about how Lexington’s 3 H’s (Horses, High tech, and Healthcare) form the foundation of our city’s economic development strategy. Those sectors may be the right ones to leverage going forward.

But when we think about stopping our exodus of talent, we need to think in more flexible terms than specific industries. A supply chain manager leaving Toyota has a unique skillset (how to get things made overseas, optimizing inventory, logistics, etc.) which can carry over to a variety of other – not necessarily high-tech – industries. A marketer leaving Lexmark has a vast array of experiences with retailers, ad agencies, design firms, and product strategy which could be redeployed to, say, UK Healthcare.

In addition to choosing strategic industrial sectors, we should also choose strategic, functional areas of expertise that we can tap into as one industry wanes and another expands. Some ideas? Supply chain, marketing, sales, engineering (multiple types), software development, etc. (Add your own in the comments below.)

Not every employee currently leaving Lexington will want to become an entrepreneur. But nearly every one wants a job.

As companies like Lexmark shrink, Lexington should seek to actively funnel their fleeing employees to growing local enterprises like Alltech, UK Healthcare, HP’s Exstream, or some new entrepreneurial venture. We should inject some “liquidity” into the local job market, so that finding local opportunities is an easier, more streamlined process. When we learn of new layoffs, our city should mobilize to keep that valuable talent local.

We shouldn’t allow employees, especially experienced ones, to leak from our economy.

3. Coordinate and amplify existing efforts. Today, we have a patchwork of agencies and institutions which have missions to grow Lexington’s economy and provide jobs. We have one person working on economic development in the Mayor’s office. Commerce Lexington is given tax dollars to help produce new jobs, but is unable to show that they have actually created any.

We should coordinate such efforts in a more strategic, consistent, coherent, and effective way. We should designate a person or an agency who has accountability for results – especially for job growth in our city. That entity should also have responsibility for fueling our entrepreneurial engine and for growing our pools of expertise.

And then – and this is really important – we must hold them accountable for the results they get.

::

The loss of 12,000 educated Lexingtonians shows us that our city needs to work hard to grow, keep, and attract talent. If we create the mechanisms to create new entrepreneurs while simultaneously magnifying our existing expertise, our economy should have the raw materials to begin growing again.

Next: 6. Be Original

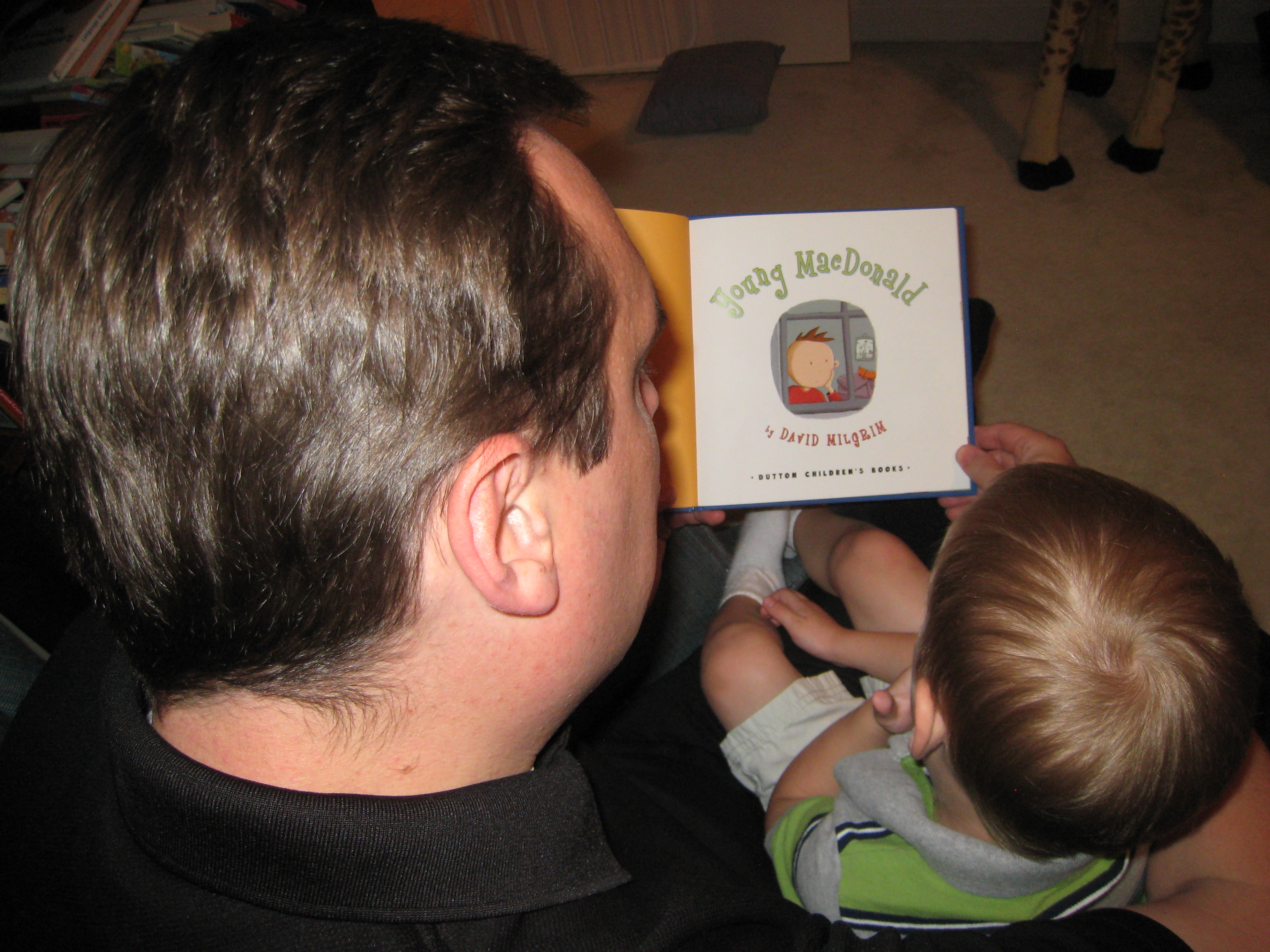

After he takes his bath and gets his pajamas on, we go to his room. I sit in the recliner, and he clambers up into my lap. We pull a book from the shelf – the books are getting longer now – and I add a bit of vocal drama as I read to him.

After he takes his bath and gets his pajamas on, we go to his room. I sit in the recliner, and he clambers up into my lap. We pull a book from the shelf – the books are getting longer now – and I add a bit of vocal drama as I read to him.