“What’s sauce for the goose is now sauce for the gander.” Indeed:

Mitt Romney’s Impressive Word Gymnastics

In the past 48 hours, we’ve seen some truly epic logical contortions from Mitt Romney’s Republican presidential campaign.

Yesterday, hoping to slow his public opinion nosedive two weeks ahead of the Michigan primary, Mr. Romney attempted to defend his infamous 2008 “Let Detroit Go Bankrupt” editorial with a second editorial in the Detroit News.

In his new valentine to Michigan and the auto industry, Mr. Romney somehow managed to simultaneously take credit for and attack President Obama’s successful 2009 bailout of the industry. Witness (my emphasis):

Ultimately, that is what happened. The course I recommended was eventually followed. GM entered managed bankruptcy in June 2009 and exited it a month later in July.

Then, two short paragraphs later:

By the spring of 2009, instead of the free market doing what it does best, we got a major taste of crony capitalism, Obama-style.

“They did what I told them to do, and it was a disaster.”

Not only was yesterday’s editorial internally inconsistent, it was also inconsistent with Mr. Romney’s 2008 editorial, which actually called for increased goverment involvement and investment, rather than simply leaving the “free market” to its own devices.

On Monday, Mr. Romney pre-empted President Obama’s 2013 budget release in an e-mail to reporters (my emphasis):

This week, President Obama will release a budget that won’t take any meaningful steps toward solving our entitlement crisis.

The president has failed to offer a single serious idea to save Social Security and is the only president in modern history to cut Medicare benefits for seniors.

I believe we can save Social Security and Medicare with a few common-sense reforms, and – unlike President Obama – I’m not afraid to put them on the table.

Mr Romney starts by attacking Mr. Obama for not addressing entitlement spending.

Then he attacked Mr. Obama again for addressing entitlement spending.

Then he attacked Mr. Obama a third time for not addressing entitlement spending.

And Mr. Romney accomplishes this amazing flip-flop-flip in three successive sentences.

And to make Mr. Romney’s linguistic artpiece even more mind-blowing: all three assertions are demonstrably false. Mr. Romney is lying.

First, President Obama’s 2013 budget proposes cutting $360 billion in Medicare and Medicaid spending over 10 years.

Second, the Affordable Care Act did not cut benefits for seniors. It created provider-side efficiencies which reduced future Medicare spending to the tune of $500 billion.

Finally, Mr. Obama proved all-too-willing to put entitlement reforms “on the table” during last year’s debt ceiling negotiations. (It is worth noting that Republicans walked away from the difficult discussions, not Obama.)

Mr. Romney was already renowned for his serial flip-flopping.

It seems that Mr. Romney has now taken his fact-free postmodern candidacy to a new plateau with his most recent linguistic art project.

His new statements don’t just thoroughly contradict previous ones; Indeed, Mr. Romney’s most recent statements thoroughly contradict themselves.

The Austerity Drag

The U.S. economy added 243,000 jobs in January, far surpassing analysts’ expectations of around 155,000 jobs for the month. As a result, the unemployment rate also unexpectedly ticked down to 8.3 percent for January.

The private sector added 257,000 jobs in January, while public-sector employment dipped another 14,000.

And that last part is important, because it begins to reveal the truly destructive nature of austerity.

Amid the wrong-headed drive to shrink the size of federal, state, and local governments (government employees make up one-sixth of the workforce), private sector job gains have been partially thwarted by the losses of government jobs.

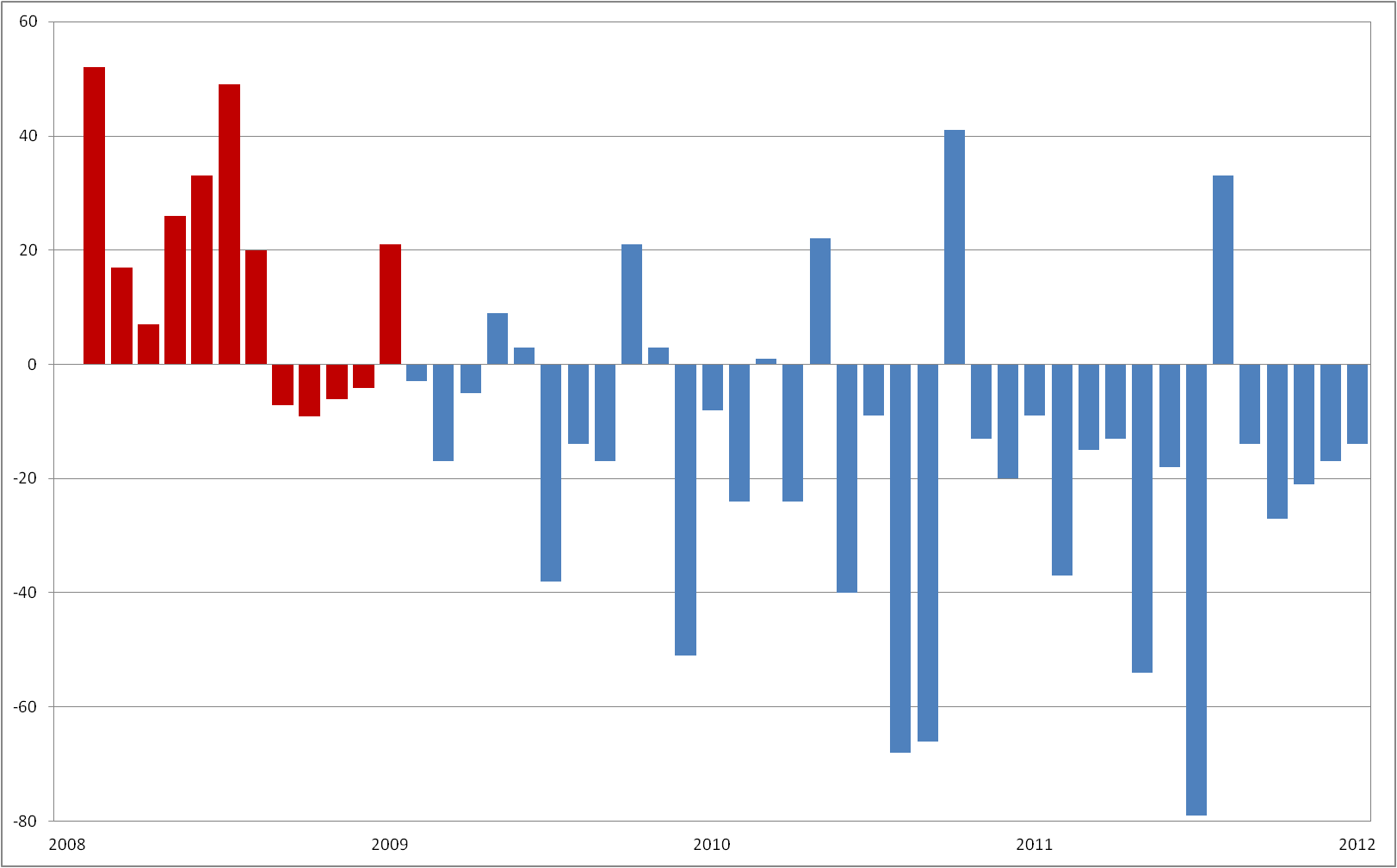

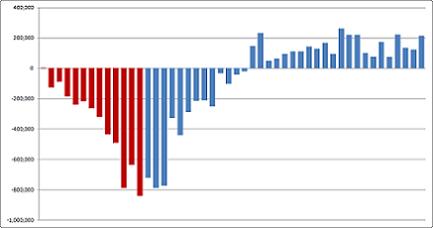

With the release of the jobs data each month, the ever-insightful Steve Benen – who joined The Maddow Blog this week – republishes his two charts showing job losses and gains for each month since the beginning of the Great Recession.

The first chart shows the overall jobs picture, while the second shows the jobs picture for the private sector alone. My shameless rip-off adaptation of these charts is below. As with Steve’s charts, the red columns show monthly job losses under George W. Bush, while the blue columns show monthly job totals under Barack Obama:

The second chart shows that the private sector has been adding jobs for each of the past 23 months.

Also worth noting: there are more total private-sector jobs today (110.4 million) than in February 2009 (110.3 million), just days after Barack Obama took office.

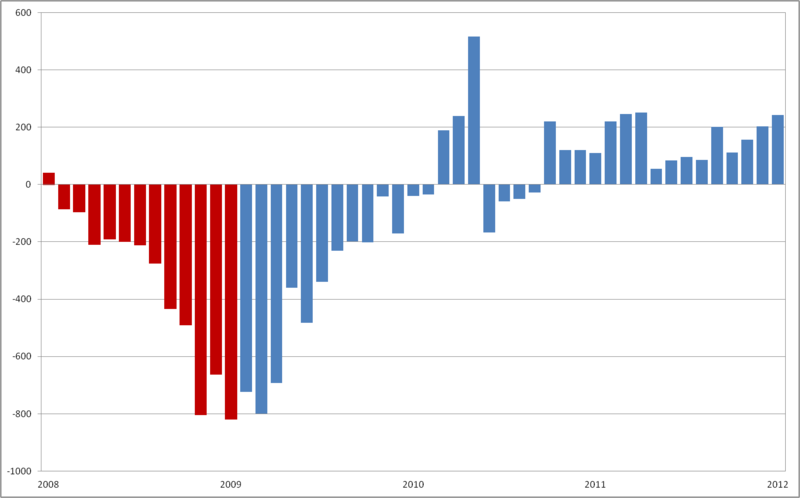

But I always wanted to see a chart which showed us what was happening in the public sector.

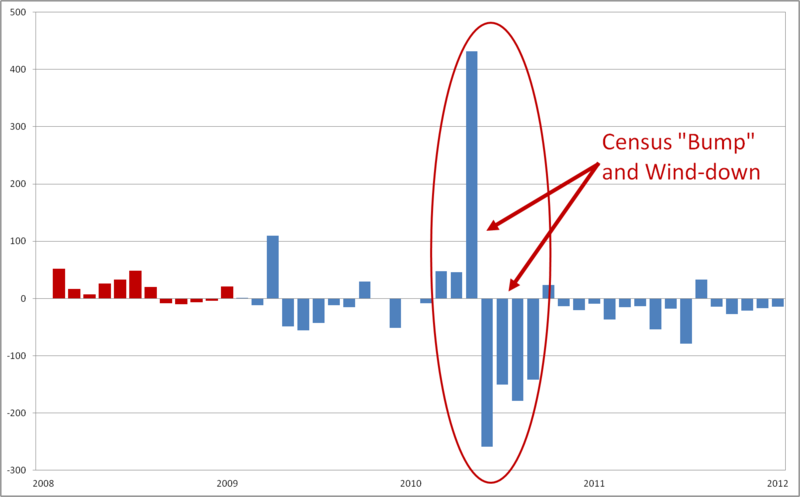

So I took matters into my own hands. Here’s my own homemade chart showing jobs totals in the public sector since the beginning of the Great Recession:

As I plotted the data, I began to understand why Steve might not show the public-sector data each month: The one-time massive hiring bump (and susequent wind-down) surrounding the 2010 Census dwarfed all of the other changes in the chart, obscuring the other month-to-month changes.

As a result, the chart provided little insight into the fundamentals of public-sector jobs.

Fortunately, the Bureau of Labor Statistics published a press package which isolated hiring for the 2010 Census. This allowed me to disentangle the one-time effects of the Census from the underlying fundamentals of public sector jobs.

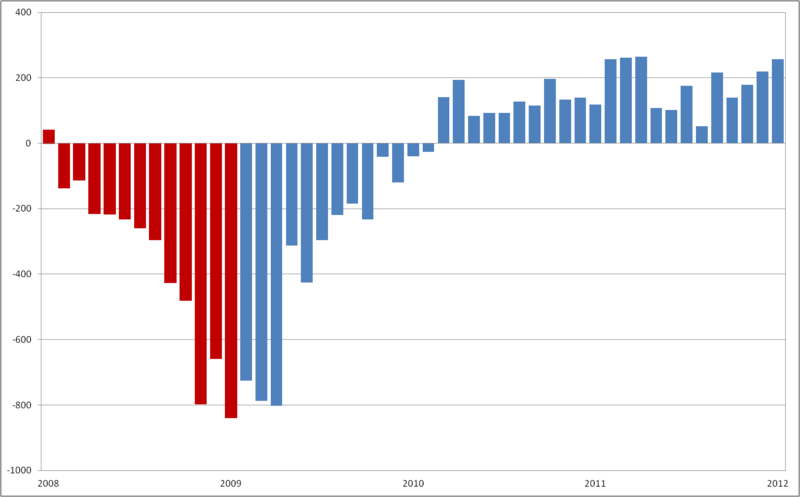

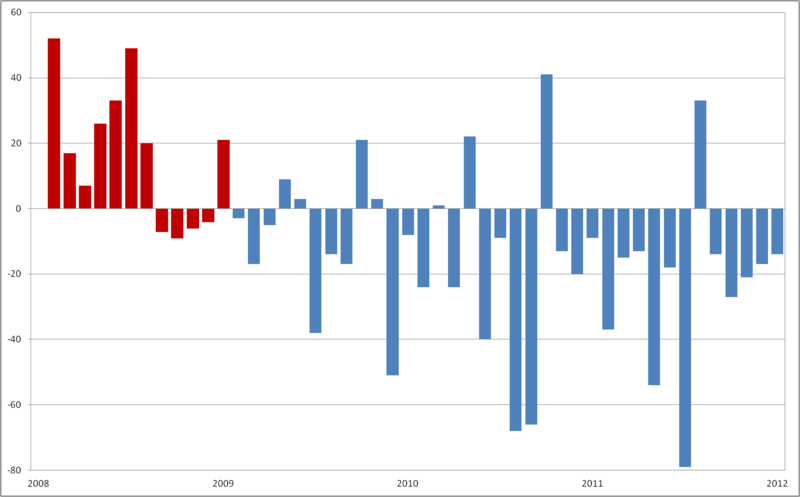

The result is this chart showing monthly job totals in the public sector, excluding the volatile Census hiring data:

In many ways, this public sector chart is the inverse of the private sector one.

At the very moment when the private sector began to recover, at the very moment the economy needed to be firing on all cylinders, at the very moment the government should have leveraged negative real interest rates* to invest in jobs and infrastructure, one-sixth of the economy was (and continues to be) stuck in reverse.

And as austerity economics kicked in, the losses in the public-sector have only deepened, creating significant drag on the economic recovery.

Since Barack Obama took office three years ago, the public sector has shed some 603,000 jobs – averaging roughly 17,000 job losses per month. (Compare that to the 840,000 public-sector jobs added during George W. Bush’s second term – an 18,000 per month clip.)

Without these public-sector job losses over the past three years, the unemployment rate would stand at 7.9% today instead of 8.3%.

While some might celebrate the wholesale destruction of government jobs, I don’t.

Public sector employees are vital to our economy and to my business. Many of my customers are teachers, first responders, court personnel, and a wide array of other local and federal government employees. Public employees create better roads and safer neighborhoods and smarter students, all of which benefits my business.

The destruction of public sector jobs negatively affects my business and our economy. As public sector employees lose their jobs, I lose business. And the wider economy suffers, as well.

Austerity just doesn’t work.

::

* A bit of explanation here on “negative real interest rates”: instead of expecting a positive return on government bond investm0ents, investors are now willingly paying to have the federal government hold their money for 5, 7, and 10 years. In essence, investors from around the world will pay us to invest in our jobs and infrastructure – which would, in turn, pay even greater dividends to our economy as we emerge from recession.

2012 and the Local Economy

I was privileged to be surveyed late last week by the Herald-Leader’s Tom Eblen for today’s column on the state of Lexington’s economy for 2012.

I don’t envy Tom: distilling the often-disparate views of eight different business owners into 800 words or less must be tough. (As regular readers might imagine, my views didn’t exactly align with many of my peers.)

My response alone was over 1000 words, so the understandable – and necessary – result was that some context was stripped from my comments.

Still, Tom asked very thoughtful questions, and I liked some of my answers. So I thought it might be worthwhile to share them here on CivilMechanics.

And if you haven’t read Tom’s column, go check it out here.

(Note: I wrote these answers early Friday morning. Some local events have already outdated at least one answer…)

1. Are you optimistic or pessimistic about the economy this year. Why?

I’m kind of bipolar on the economy. For the first time in 4 years, I’m seeing signs of strength in our business, in our customers and their ability to buy our services, and in the national economy.

At the same time, I see two major “storms” on the horizon: the apparent willingness of Republicans in Congress to scuttle the economy for political advantage (and I don’t think this is a “both sides” thing – see this, for example), and the apparent unwillingness (or inability) of Europe to deal effectively with their debt crisis.

In my view, both storms are fueled by wrong-headed drives for austerity – forcing governments to spend less when no one else is spending, and further drying up demand.

2. How is your business doing? How are business conditions better or worse for you than they were a year ago?

Our business is still weaker than I’d like in the wake of the recession, but it is growing. Sales are up about 3% over last year, but some of the underlying fundamentals still aren’t where they need to be. While we’ve seen some improvement, many of our customers are still delaying basic maintenance on their cars because they can’t afford it.

3. What’s your biggest business concern for the coming year?

I’ve hired two new technicians in the last 9 months, including one last week, bringing us to six mechanics in total. Having more technicians will help us enormously in the busy spring and summer months. But the winter is typically our slowest time of the year, so bringing on an additional employee now is a bit of a risk: Will there be enough work to keep everyone busy and happy? Will there be enough business for me to make a profit while paying them?

Getting through the next few months with a bigger staff is my biggest current concern. Keeping them busy throughout the year by bringing customers through the door is my biggest concern for 2012.

4. What do you see as your biggest opportunity for the year?

Having a larger staff will allow us to serve more customers more quickly. Toward the end of 2011, we were frequently scheduling appointments up to a week in advance because we were too busy to get customers into the shop sooner, and we lost some business because we couldn’t get them in right away. We want to improve our service and accommodate our customers more quickly in 2012, and the additional employees will help us with that.

5. What would you like to see the president and/or Congress do to improve the economy?

I’d like to see another massive stimulus package.

While it may not be popular with your readers, there is no doubt that the early 2009 stimulus worked. (See chart of private-sector job losses and gains at right, stolen from the estimable Steve Benen.) We were losing hundreds of thousands of jobs every month and the economy was imploding. Immediately after the stimulus, the economy stabilized and the jobs losses dropped dramatically, and jobs have been growing slowly and steadily since early 2010. But a stable and slow-growing economy isn’t enough. I’d like to see another stimulus to help jump-start a more dynamic, fast-growing economy.

A lot of folks will say that we need to cut taxes and regulation in order to get the economy growing again. That’s a head-scratcher for me. Lowering my taxes and putting a little extra money in my pocket won’t help me create a job. Neither would letting me pollute more.

I’ve hired two new employees in the last year (growing 25% from 8 employees to 10), and the decision to hire them was driven by customer demand for faster and better service – which had nothing to do with my taxes or regulations. Customer demand drives hiring; giving business owners extra money or convenience really doesn’t.

I like President Obama’s American Jobs Act as a starting point for a stimulus – investment in infrastructure, schools, and public safety is a sound way to grow economic demand. But I’d like to see even more investment in other areas, such as energy research and American manufacturing, and I’d like to see a stimulus closer to $1 trillion to really get the economy growing again.

That’s what I’d like to see. I see zero chance of this actually happening with this Congress.

6. Will this year’s presidential election make the economy better or worse? Why?

I fear that it will make things worse, at least for the short term. It is hard to imagine how our political system could be more gridlocked than it was in 2011. Still, as congressional Republicans obstruct any initiative which might make the President look good, I worry that they’ll sacrifice the economy on the altar of politics.

As for the race itself, I see a worrying thread of extremism from the GOP candidates. Even the supposedly-moderate Mitt Romney is proposing extreme policies which benefit the wealthy even more and skewer the middle class and poor even more (thereby skewering most of my customers). I worry that the austere policies a Republican President might attempt to implement would decimate my customer base and my business.

7. What is Lexington’s biggest asset during these economic times? It’s biggest problem?

I think our schools – particularly UK – are our biggest asset. They provide our city with well-educated people, great research to improve our lives and build businesses upon, and a vibrant “student economy” which spills over into the rest of our city.

I see two big problems for Lexington. First, if the proposed redistricting is approved by Governor Beshear, a huge chunk of our city will not be represented in the Kentucky State Senate for two years. Proper representation in Frankfort is vital to protecting Lexington’s interests and to protecting UK, and these undemocratic redistricting plans would deprive one-third of our city of its vote. I worry about the impacts of Lexington not being represented in Frankfort.

Second, I think our city, our state, and our schools are under-funded. I appreciate all of the efforts Mayor Gray has made to trim Lexington’s budget, but at some point, we citizens need to fund all of the services and infrastructure and improvements we’ve come to expect.

I want nice roads for me, my customers, and my employees. I want them to be plowed and salted when nasty weather strikes this winter. I want the best schools for my son and for my employees’ families. I want the best fire and police protection. I want a beautiful and safe city to live and work in. But those benefits come at a price. And we’re responsible for funding all of those “nice things”.

It won’t be popular, but I think we need to start a frank conversation about raising taxes to fund our city’s (and state’s and schools’) obligations. We need to pay for the great things we want to do together.

8. What else should readers know that I haven’t asked about?

I hope they’ll go out of their way to buy local goods and services when possible. That will keep more of Lexington’s money in Lexington, which helps foster a more vibrant local economy.

The 1345

Mitch McConnellYesterday, despite having support from a majority of the Senate, the $60 billion Rebuild America Jobs Act was blocked from even being debated on the floor of the Senate by Kentucky’s own Mitch McConnell and Rand Paul – along with every other Republican senator.

The Act included $50 billion in direct spending for roads, bridges, and other infrastructure, as well as $10 billion towards starting the National Infrastructure Bank. Both ideas have traditionally enjoyed bipartisan support.

The bill would be paid for by a 0.7% surtax on incomes over $1 million.

The Department of Transportation estimated that the Act would create about 800,000 new jobs.

McConnell was unapologetic for blocking debate on the bill:

“The truth is, Democrats are more interested in building a campaign message than in rebuilding roads and bridges,” said Senate GOP Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky. “And frankly, the American people deserve a lot better than that.“

800,000 jobs seems like more than a campaign message.

But these national numbers are a bit hard to get our arms around.

It’s worth evaluating the impacts of this bill on a more local level. What would the Act do here in Kentucky?

Over 200,000 Kentuckians are out of work. That’s nearly 10% of the labor force.

And since September, one of two major bridges crossing the Ohio River in McConnell’s hometown of Louisville has been shut down after inspectors found cracks. Another bridge between Kentucky and Cincinnati has been deemed “structurally deficient”.

Rand PaulThe bill McConnell and Paul voted against would have spent over $450 million on roads and bridges in Kentucky, and would have created 5,900 jobs.

Why would Mitch McConnell and Rand Paul reject 5,900 jobs for Kentucky? Why would they oppose fixing Kentucky’s infrastructure?

Maybe they’re concerned with raising taxes. As McConnell said on Meet the Press, “We don’t want to stagnate this economy by raising taxes” on those who make over $1,000,000, who Republicans are fond of calling “job creators” and “small business owners”.

So let’s take a look at who makes over $1,000,000 in Kentucky. According to Citizens for Tax Justice [PDF Link via Greg Sargent] out of Kentucky’s 4.3 million citizens, there are 1345 Kentuckians who would be affected by such a tax, and they make an average of nearly $3.5 million.

And it’s worth noting that The 1345 are folks who don’t just have $3.5 million – enough to qualify them as multi-millionaires. These are people who clear $3.5 million per year.

The 1345 are the ultra-wealthy. And businesses which help their owners reap $3.5 million per year are not ordinarily considered “small”.

And what is the onerous burden the “millionaire’s tax” would place on The 1345?

Out of their $3.5 million in income, The 1345 would pay $17,409 more to fix Kentucky’s roads and bridges which they undoubtedly benefit from more than Kentucky’s other 4,338,000 citizens.

So: McConnell and Paul blocked the creation of 5,900 jobs and the improvment of roads and bridges for all Kentuckians in order to protect The 1345, a tiny group of ultra-wealthy Kentuckians who would pay only $17,409 to rebuild the infrastructure they use more than anyone else.

McConnell claims he doesn’t want to “stagnate the economy” by taxing The 1345, which raises the question: What have these ultra-wealthy “job creators” been doing with this money while they’ve kept it?

Because they certainly haven’t been creating jobs.

Mitch McConnell and Rand Paul chose to protect The 1345 at the expense putting 5,900 Kentuckians back to work. At the expense of our crumbling roads and bridges. At the expense of the other 4,338,000 Kentuckians.

And frankly, the American people – and Kentuckians – deserve a lot better than that.

The American Idea

My wife and I are one-percenters.

We have amassed a small fortune – built over some 20 years of climbing our respective corporate ladders, saving very aggressively, and making some favorable investments.

We worked very hard to build our wealth.

But we are also incredibly lucky.

We were both winners of what Warren Buffett has dubbed “the uterine lottery”: through no effort on our part, we were both born into safe, stable, American, loving family environments where hard work and academic success were built-in expectations. We were granted this huge headstart in life and had no part in earning it.

That early headstart only snowballed as it helped us accumulate advantage upon advantage in our early lives.

We benefitted greatly from our society’s investments in all sorts of public goods, public works, and public innovations.

More bluntly, because of our unearned headstarts, we benefitted disproportionately as we often extracted more value and more opportunity from these public goods than did our less-advantaged peers.

In our youth, we both got into honors-level courses at great public schools. We both had great professors at our public universities, where we both received advanced degrees.

In our professional lives, we continued our disproportionate wins, taking greater advantage of public investments in roads, airports, research, computers, the Internet, housing, and police and fire protection.

As a business owner, I continue to receive disproportionate share of the benefits from the public investments which deliver customers and vehicles and qualified employees into my shop.

My wealth is – in great part – the result of decades of personal hard work, constant learning and creativity, and deep thought.

But my wealth is also the product of decades of unearned advantage which allowed me to receive an undeserved greater share of our society’s prosperity.

For my disproportionate bounty, I owe a disproportionate debt.

::

This “disproportionate debt” is the basis of the American system of progressive taxation – the reason that those with higher incomes and greater wealth pay taxes at higher rates. The wealthy owe more to the nation which co-produced their wealth.

As President Obama’s jobs proposals and the Occupy Wall Street protests have gained favor among independents and an increasing proportion of Republicans, the national conversation has begun to focus on the responsibility of the wealthy in creating, perpetuating, and resolving our current economic woes.

In polls, the overwhelming majority of Americans support greater public investments in infrastructure, education, and public safety in order to create jobs. And they support raising historically-low taxes on the wealthiest Americans to do it.

And yet, an increasingly-prominent conceit of conservative ideology holds that every person is merely the product of their own singular efforts, and that those with success owe nothing (or owe very little) to the society which made their success possible.

Purveyors of this ideology live in a kind of denial – conveniently ignoring the significant roles of simple luck, coupled with public investments in infrastructure, education, and research, in improving their own lives and in enabling the lives of the wealthy. They contend that the wealthy pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, and everyone else should as well.

After Warren Buffett – history’s most successful investor – argued in August that the very wealthy have a duty to pay more in taxes, Harvey Golub – former Chairman and CEO of American Express and former Chairman of AIG – expressed the “bootstraps” mentality in his opening to an indignant Wall Street Journal screed [emphasis added]:

Over the years, I have paid a significant portion of my income to the various federal, state and local jurisdictions in which I have lived, and I deeply resent that President Obama has decided that I don’t need all the money I’ve not paid in taxes over the years, or that I should leave less for my children and grandchildren and give more to him to spend as he thinks fit. I also resent that Warren Buffett and others who have created massive wealth for themselves think I’m “coddled” because they believe they should pay more in taxes. I certainly don’t feel “coddled” because these various governments have not imposed a higher income tax. After all, I did earn it.

The corollary to Golub’s “I earned it” meme is that poverty and joblessness are presented less as a result of unfortunate circumstance than they are as a reflection of moral failings on the part of the poor or unemployed.

When asked about the Occupy Wall Street protests, for instance, GOP presidential candidate Herman Cain told the Wall Street Journal [emphasis added]:

“Don’t blame Wall Street, don’t blame the big banks, if you don’t have a job and you’re not rich, blame yourself!”

At a book signing in Florida one day later, Cain added that the OWS protesters were un-American and anti-capitalist for protesting against Wall Street banks because “they’re the ones who create jobs” – despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. At a Republican debate a couple of weeks later, Cain was asked if he stood by his remarks, and his affirmation garnered the night’s biggest applause from the partisan crowd.

But perhaps no one in today’s politics defends the rights of the wealthy quite like Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan. Ryan, who requires his staff to read Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged for its policy insights, is the chair of the House’s Budget Committee.

But perhaps no one in today’s politics defends the rights of the wealthy quite like Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan. Ryan, who requires his staff to read Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged for its policy insights, is the chair of the House’s Budget Committee.

Ryan is well known – and mystifyingly well-regarded as a “serious thinker” – for his attempts to use the budget process to accelerate social inequality. Ryan’s 2011 budget plan, dubbed The Path to Prosperity, was an audacious reverse-Robin-Hood attempt to slash safety nets for the most vulnerable even as it it further slashed taxes for the already-wealthy.

With the President’s jobs agenda and the Wall Street protests gaining popularity, and the national conversation now squarely focused on jobs and inequality, Republicans have been losing control of the political narrative they dominated during this summer’s debt crisis.

In a much-anticipated speech, “Saving the American Idea: Rejecting Fear, Envy, and the Politics of Division”, delivered to the conservative Heritage Foundation last week, Ryan attempted to recast that narrative with an ideological agenda nearly worthy of an Ayn Rand protagonist.

In that speech, Ryan outlined the American Idea as defined by the “principles of free enterprise, limited government, individual freedom, traditional American values, and a strong national defense”.

After chastising the President for promoting his jobs initiatives while “sowing social unrest and class resentment,” Ryan laid out the contours of his new narrative.

The central problem of economic justice in America doesn’t revolve around a wealthy class which isn’t doing its part, Ryan asserted, but around a social welfare system which inhibits economic opportunity and economic mobility. Ryan contends that progressives don’t understand this because they confuse “equality of opportunity” with “equality of outcome” [emphasis added]:

These actions starkly highlight the difference between the two parties that lies at the heart of the matter: Whether we are a nation that still believes in equality of opportunity, or whether we are moving away from that, and towards an insistence on equality of outcome.

If you believe in the former, you follow the American Idea that justice is done when we level the playing field at the starting line, and rewards are proportionate to merit and effort.

If you believe in the latter kind of equality, you think most differences in wealth and rewards are matters of luck or exploitation, and that few really deserve what they have.

That’s the moral basis of class warfare – a false morality that confuses fairness with redistribution, and promotes class envy instead of social mobility.

There are a couple of major problems with Ryan’s new “equality of opportunity” narrative.

First, the playing field is never level at the starting line. Unmerited inequalities exist, and they often grow exponentially over time.

Ryan would have us believe, for instance, that a child born some forty years ago with dark skin to an impoverished single mother in, say, inner-city Detroit had all of the same advantages and opportunities afforded to a child born some forty years ago into a stable, upper-middle-class white family in, say, Janesville, Wisconsin.

The circumstances of the starting line matter. And it is all-too-convenient for those given headstarts to pretend they don’t.

Second, economic justice doesn’t stop at the starting line. We must also assure that the race is run fairly.

Running the race fairly isn’t about insuring “equality of outcome”, as Ryan contends. Most participants will not “win” the economic race. But it is about making certain – through establishment and enforcement of the rules – that participants do not cheat or exploit one another. It is about making certain that we flatten very real hurdles of race, gender, and income (to name just a few).

And asking the wealthy to pay disproportionately into the system which helped provide their disproportionate prosperity isn’t “redistribution” – it is merely the repayment of a disproportionate debt. It is fairness.

::

I’m sure that Harvey Golub, Herman Cain, and Paul Ryan all worked incredibly hard to achieve their successes. But somewhere along the way, as they deified their individual efforts and accomplishments, they forgot – if they ever recognized in the first place – the enormous and undeniable roles that luck and public welfare played in their successes.

In a town hall two weeks ago, for example, Ryan told a student that the Pell Grant program (federal assistance for lower- and middle-class students) was “unsustainable”, and Ryan noted that he worked three jobs to pay off his student loans. Good for him.

But Ryan also leveraged his public school and public university education to get his start in Washington. And while he promoted his private sector student loan as some sort of ideal, Ryan failed to mention that he also used his father’s Social Security death benefits to help pay for college. He went on to a taxpayer-supported career in Washington, including the last 13 years as an employee of the very government he regularly demonizes.

With no trace of apparent humility for their remarkable good fortune (nor apparent blush for their remarkable hypocrisy and greed), these successful men promote the mythology of the completely self-made success.

But no one with wealth got that wealth solely on the basis of their own virtues. On their paths to success, each got help – sometimes deserved, often not. To ignore the help we have received is to ignore our obligations to one another. Worse, it betrays an unfortunate ungratitude.

The wealthy and successful extract greater value (and wealth and success) from our public goods, and thus owe a greater debt to the communities which contributed to their successes.

::

Paul Ryan is right, but inadequate: the American Idea does revolve around rewarding individual merit, effort, and ingenuity. But that isn’t all. That isn’t nearly enough.

The American Idea also revolves around our ability to work together to do and build great things. Our civic commitments to greatness – especially in times of crisis – mark our national identity and our national success every bit as much as (maybe even more than) our individuality does.

Many of our nation’s greatest accomplishments – Social Security, Interstate highways, successes in World Wars I and II, the Civil Rights Act, National Parks, and even the free enterprise system itself – are built upon a foundation of mutual cooperation and mutual sacrifice.

The American Idea is simply not the either-or cartoon presented by Paul Ryan.

We are a great nation because of our individual efforts, of which we are justifiably proud. And we are a great nation because of our mutual commitment to one another, of which we are profoundly humbled. We must ensure both to build upon our greatness.

That is an American Idea worth saving.

::

One final note: I find it increasingly difficult to tolerate condescending, one-sided lectures on the virtues of individual effort and private enterprise (and on the evils of “redistribution”) when they come from political mercenaries who have financed their professional careers with public money.

And, yes, I’m looking at you, Paul Ryan.

Confessions of a Job Creator

I’m a job creator. And job creators are important.

At least that’s what we’ve been hearing from Republicans lately.

House Speaker John Boehner cited “job creators” and “job creation” 26 times in a speech about the economy last week.

And in that speech, the Speaker invoked us job creators to attack the Republicans’ Unholy Trinity: taxes, regulation, and government spending:

Private-sector job creators of all sizes have been pummeled by decisions made in Washington.

They’ve been slammed by uncertainty from the constant threat of new taxes, out-of-control spending, and unnecessary regulation from a government that is always micromanaging, meddling, and manipulating.

To hear Boehner’s version of events, the government stands as the sole obstacle to us job creators as we valiantly attempt to create more jobs.

Indeed, the entire Republican establishment keeps talking about the special role we job creators play in our fragile economic recovery.

In their “House Republican Plan for America’s Job Creators” – a 10-page, large-type tome [PDF link] about the same length as this blog post – the House Republican leadership repeatedly promise to slash the Unholy Trinity of tax, regulation, and spending. On Sunday talk shows, more of the same.

If only we job creators paid less money in taxes, Republicans say, we would hire more.

If only we were free from government regulation, we would hire more.

If only we were less concerned about government spending, we would hire more.

As much as I appreciate Republicans’ apparent concern – their willingness to dump money in my pocket, their longing for my freedom to pollute with abandon, their eagerness to drive the nation to the edge of default to keep government spending in check – here’s the thing:

Their efforts won’t help me create a single job.

Not one.

In fact, Republican attacks on taxes, regulation, and spending do quite the opposite, because Republicans are thoroughly wrong on the mechanics of hiring.

I don’t hire because I have extra jingle in my pocket. I don’t hire because I can avoid complying with some regulation or tax. I don’t hire because the government is spending less. I hire because there’s more work to do.

No responsible businessperson is going to hire simply because they have extra money lying around or because they can dump motor oil in the sewer. As generous as I might be, I won’t hire out of charity.

Entrepreneurs hire because they have work to do, and a new employee can help them get that work done. They hire to help meet demand. And demand is fueled by customers who have money to spend.

And that’s the fallacy of the Republican job creator mythos: Job creators don’t “create” jobs. Our customers do.

And the evidence proves the Republican fallacy. Taxes are at historic lows [PDF link]. Corporate profits are at record highs. Government spending has collapsed. These are the very conditions under which, according to Republicans, we job creators should be creating jobs.

But we aren’t.

Despite these supposedly wonderful conditions for job creators, one in six Americans remain unemployed or underemployed. Income and household wealth has stagnated for over a decade. Instead of hiring in this environment, corporations are hoarding record stockpiles of cash in the face of weak demand.

No demand, no jobs.

That’s not to say that we entrepreneurs – let’s just drop the “job creator” garbage – are powerless. We can foster conditions which promote growth (the right business model, the right service, the right people); but we need customers with a willingness to spend to make our businesses grow and to create an environment where hiring is possible and profitable for us.

Bottom line: Give me money, and I’ll sock it away in the bank. Give me customers, and I’ll give you jobs.

Introducing CivilMechanics

Since its inception three years ago, the Lowell’s blog (blog.lowells.us) has been a strange beast.

It has been an admixture of news about Lowell’s, tips for car maintenance, thoughts about business and the economy, and assorted commentary on our community, on downtown, and on the city of Lexington.

While this assortment was in line with our stated intent to offer “our perspectives on cars, business, Lexington, and life,” it also resulted in a divided audience: those who care about cars and what is happening at Lowell’s (usually customers); and those who care about more civic matters.

As you might imagine, the practical overlap between these groups is quite small. The car folks probably don’t care about musings on CentrePointe or Lexington’s streets and roads. The civic folks probably don’t care about what’s happening with the Lowell’s website or how a brake flush works.

Still, I could kind of rationalize the Lowell’s blog as a local blog by, for, and about a local business and local issues.

::

I have been the sole contributor to the Lowell’s blog. And over the past year or so, my postings have been far less frequent than I’d like.

Part of that has to do with the busy-ness of our business (I haven’t had as much time to devote to writing), but most of it lies in the fact that I’ve been wanting to write about new and different things.

In particular, I’ve wanted to shift my focus from predominantly local issues to predominantly national and global ones – to try, for instance, to decode what’s happening in Washington or Wall Street from my own distinct perspective. These topics just didn’t feel at home among car care tips and shop news.

At the same time, I’ve wanted to extend the content of the Lowell’s blog to include new contributions and new kinds of content from my employees here at Lowell’s. As I contemplated such a move, I didn’t want them to feel overshadowed by strongly-expressed views which they might not share.

To resolve this dilemma, I’ve created a new blog called CivilMechanics (www.civilmechanics.com) – sponsored by Lowell’s – in which I will express my unique perspectives on a variety of issues. (And, yes, “CivilMechanics” is an intentional multiple-entendre. I like that kind of stuff.) Please check out our first post, “Confessions of a Job Creator“.

To resolve this dilemma, I’ve created a new blog called CivilMechanics (www.civilmechanics.com) – sponsored by Lowell’s – in which I will express my unique perspectives on a variety of issues. (And, yes, “CivilMechanics” is an intentional multiple-entendre. I like that kind of stuff.) Please check out our first post, “Confessions of a Job Creator“.

I’ve also taken the liberty of migrating a few old Lowell’s posts to CivilMechanics which capture some of the spirit of this new blog.

Over the coming weeks, we’ll introduce new contributors to the Lowell’s blog. I’ll also continue to post on the Lowell’s blog from time to time with items of interest to Lowell’s customers and Lexingtonians.

With these changes, I’m hoping to increase our overall frequency of posts, both for customers (through the Lowell’s blog) and for civic-minded followers (through CivilMechanics). Please check them out, and be sure to let us know how we’re doing.

The Lowell’s Blog: blog.lowells.us

CivilMechanics: www.civilmechanics.com

And now for the hard part…

Critics have identified three interrelated categories of problems for CentrePointe since it was introduced to the public in 2008:

- Context. Will it ‘fit’ with downtown Lexington?

- Financing. Will it be built?

- Viability. If built, will it work?

And CentrePointe has consistently failed across all three dimensions. It didn’t fit Lexington. It couldn’t be financed. And it wasn’t viable.

As the project has changed trajectory in the past few months, it is worth re-examining these critiques.

Context

The first three iterations of CentrePointe were uninspired and uninspiring. The designs seemed devoid of place – as though they could be plopped down on any block in any random city – Nashville, Atlanta, Phoenix, Detroit. There was nothing about the designs which was particular to Lexington.

The bland and imposing structures were also the architectural equivalents of bullies – crowding Main Street, unwelcoming to pedestrians, overshadowing nearby buildings, and oblivious to the surrounding fabric of downtown.

The heavy-handed designs seemed to mirror the developers’ if-you-don’t-like-it-well-that’s-just-too-damn-bad demeanor.

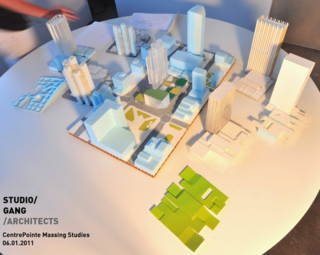

In recent weeks, however, we have begun to see much more hope for CentrePointe. With help from the mayor, the developers engaged Chicago’s Studio Gang Architects (SGA) to reconceive the site. And the developers have interacted much more with the public and the press – including a quasi-interview with the developer which utilized our questions from an earlier post. (We’d like to ask some follow-ups!)

Jeanne Gang presented her firm’s initial architectural concept for the CentrePointe block to a packed crowd at the Kentucky Theatre last week.

It was a great design.

And like most great designs, it poses elegant solutions to several problems at once. Here are a few highlights which caught our attention:

And like most great designs, it poses elegant solutions to several problems at once. Here are a few highlights which caught our attention:

- Mass. SGA departed from previous monolithic designs, and redistributed the mass of the project across the site. The new asymmetric distribution allows the design to accomplish a number of goals. Breaking the project into components also opens the possibility that the site might be developed in phases – perhaps as financing becomes available.

- Main Street. Along Main Street, SGA proposes having 6 distinct building designs which would mirror the varied designs across the street and which would also help maintain the organic, eclectic feeling of a typical Main Street.

- Inclusiveness. To help ensure distinct building designs along Main Street, SGA has selected five local architects to design 5 of the 6 buildings on that side of CentrePointe.

- Plays Nice. Unlike the earlier “bully” designs, this one seems to play nicely with the surrounding city. SGA used “shadow studies” to assess how the 30-story tower might throw shadows over nearby buildings. Those studies helped them decide to place the tower near the corner of Upper and Vine Streets, where the building would be less overpowering on the surrounding blocks.

- Circulation. This design also departs from earlier versions in that it promotes pedestrian circulation with the surrounding city and within the site, with ample open spaces and public areas. It is able to accommodate parking access for cars without significantly disrupting pedestrian access.

- Lexington. Studio Gang are trying to give the project local meaning – connecting it to our history, stories, and environment. And while I’m skeptical of the real utility of “the connected separateness of paddocks” or “the porosity of limestone” as sources of inspiration for the new design, SGA is the first CentrePointe architect who seems to realize that it will be built in a unique setting within our unique city.

Studio Gang have crafted this particular design to this particular spot in Lexington, and the result is very encouraging. Lexington may finally have a signature project worthy of the center of our city.

Financing

The changes in the nature of the CentrePointe project don’t alter the economic environment for getting the project funded.

While now armed with a world-class architect and a world-class design, the developers are still faced with the enormous challenge of finding funding while the commercial real estate market remains in severe recession.

Investors will be far less interested in the aesthetics of the project than its financial viability as an investment vehicle…

Viability

Our central criticism of CentrePointe over the past few years has been its economic viability. We’ve spent a lot of time deconstructing the economics of CentrePointe, and whether it can ‘work’ as an economic entity.

In short, the project wasn’t – and still isn’t – realistic.

Each of the four components of the project (condominiums, hotel, retail, and office) demanded exceptionally high prices and required exceptionally high occupancy to be successful.

Despite the inclusion of SGA in the design of CentrePointe, the developers won’t be able to achieve the levels of occupancy needed to make the project successful. (Both prices and occupancy were far in excess of the Lexington market.)

The project also needed the infusion of Tax Increment Financing (TIF) from the state and city to help pay for ‘public’ improvements to the site (including sidewalks, parking garage, storm sewers, and other infrastructure).

The city and state would issue TIF bonds (debt) to pay for today’s improvements, and would pay them back with interest by harvesting future tax revenues coming out of the CentrePointe site.

And, as we have shown before, the CentrePointe TIF – based on incredibly optimistic assumptions – never pays back the city or state for their investment. In essence, TIF amounts to corporate welfare for the developers.

And no knowledgeable bond analyst would ever recommend the CentrePointe TIF to his or her investors. It would never pay them back.

::

Over the past three years, CentrePointe seemed like a lose-lose for Lexington: We lost if the project wasn’t built; we lost if it was built, too.

CentrePointe was a bad idea. And it was badly executed.

The new approach to designing CentrePointe is different: This new design incorporates so many great ideas, and it seems to function so well with downtown Lexington.

Studio Gang has helped transform the threefold criticism of CentrePointe – It doesn’t fit Lexington; It can’t be financed; It isn’t viable – into a twofold critique. CentrePointe still can’t be financed. It still isn’t viable.

While still deeply skeptical about the project’s economic viability (and its value for Lexington), we find ourselves pulling for this vision of the project – just a little.

This CentrePointe seems like a good idea – maybe even a great one. And that’s the first time we can legitimately say that about CentrePointe.

But great ideas are the easy part.

Now, the community’s attention must turn to the hard part of CentrePointe: Execution.

The transition to execution poses new challenges for the developers and for Studio Gang.

How will the project find funding? Can they conceive a more realistic plan which pulls back from today’s more ambitious design? Can they make a 20-story tower work, for instance? Can they craft an economic model which doesn’t rely so heavily on TIF? Can they build smaller parts of the project today, and finance the rest when the economy improves?

The future of downtown might rest on the answers.

UPDATE 7/18/2011: Jeff Fugate has an excellent post on what the new design of CentrePointe accomplishes over at ProgressLex.

The Promise (and Predicament) of CentrePointe

Since CentrePointe was initially proposed over three years ago, the project has been marked by fantastical bluster, broken promises, poor designs, and, ultimately, a failure to build. All of which was compounded by the developers’ riteously indignant, arrogant, and combative attitude when challenged on the wisdom of CentrePointe.

A couple of years ago, after declaring CentrePointe an impossible-to-build failure, we outlined some basic principles for reconceiving the (still) empty block in the heart of our city. Here’s an abbreviated excerpt from that post:

- Create a vibrant destination which attracts residents, workers, and tourists.

- Make that destination a distinctive place which no other city has.

- Create public and private spaces within the destination.

- Balance the types of uses within the development.

- Ensure local businesses have significant presence.

- Ensure that the space is well-integrated with the surrounding community.

- Build it soon.

After three years of apparent tone-deafness by CentrePointe’s developers, the prospects for such a “signature place” seemed quite dim.

::

On the sweltering third floor of the old courthouse yesterday, an overflow crowd of some 300 Lexingtonians received a tantalizing glimpse of a new approach to the CentrePointe project.

And that approach represented an enormous (and refreshing) step in the right direction.

With the encouragement of Lexington’s new mayor, the developers engaged Jeanne Gang of Chicago’s Studio Gang Architects (SGA) to rethink the CentrePointe block.

On Thursday, she present preliminary site design concepts for the CentrePointe block. And she presented a marked departure from the old approach to CentrePointe.

Gang’s presentation and the developers’ new approach are refreshing in a number of ways:

Gang’s presentation and the developers’ new approach are refreshing in a number of ways:

- Design. SGA abandons the “Fortress Lexington” approach of the old CentrePointe. By breaking the project into independent components with different volumes and designs, SGA will avoid the imposing and monolithic designs offered in previous iterations of CentrePointe.

- Openness. By showing preliminary design concepts and inviting public input on them, CentrePointe promises to be a much more open project. The developers are even inviting local architects to design the Main Street components of the project.

- Humility. Gang showed her work and her thinking while it was still in progress, while it was still incomplete. Exposing this level of uncertainty takes a striking degree of humility and confidence – for both the architect and the developer. Whereas previous iterations of CentrePointe were presented as a fait accompli to be adored by a passive audience, SGA’s version promises to be a shared community treasure which we might be able to design together. In this more humble regime, once-adversarial relationships might transform into more-cooperative ones.

The mayor and the developers and SGA are to be commended for crafting this new approach to CentrePointe.

The chances for creating a unique, signature place for Lexington went way up yesterday. And the developers deserve some credit for allowing that to happen.

::

Despite the new approach to designing CentrePointe, a number of nagging issues remain for the tortuous project.

While Gang’s site design breaks up the monolithic tower of previous CentrePointe concepts, it appears to maintain the overall square footage and volume of the last iteration of the project. If the project is roughly the same size, it should be roughly the same cost – around $200 million.

And if the developers have had difficulty lining up financing for the past three years, what will allow them to line it up now? The commercial real estate market remains deeply depressed, and it isn’t clear that such abundant premium space would find tenants in Lexington. The business model issues we identified early in the project haven’t fundamentally changed.

Is it possible that the new design will be so revolutionary, so inspirational, so great that investors and tenants will line up around the CentrePointe block to get in? Perhaps. We’d be thrilled. But we doubt it.

The $200 million price tag is also important because that is the minimum required to qualify for tax increment financing (TIF). TIF allows cities and states to allocate future incremental tax revenues to finance today’s public improvements related to new economic development initiatives.

In CentrePointe’s case, the city and state would finance about $50 million in improvements – a parking garage, sidewalks, storm sewers, etc. – around the project, and they would hope to recoup that investment from new taxes generated by CentrePointe. In previous analysis, we’ve found that the CentrePointe TIF is highly problematic, and that it is doubtful that the city or state would ever get their money back.

Even though the new design direction is encouraging, several other aspects of the project are still unresolved. Is the project the appropriate scale for Lexington? Can it find willing tenants? Can the developers nail down financing? Is the TIF worth the up-front expense?

The developers find themselves in a dilemma: If their project falls below the $200 million mark, it will be much more realistic to finance and to find occupants. But it will lose the $50 million boost from TIF financing.

If the project comes in over $200 million, it is much more difficult to finance and occupy, and the opportunity for financing the project in the next 5 to 6 years looks grim. (The TIF agreement between the Kentucky Economic Development Finance Authority and the city specifies that the $200 million be spent by January 2015).

::

We applaud the developers’ new, more-open approach to designing CentrePointe. Bringing Jeanne Gang and SGA in to rethink the site is a welcome departure from the past three years. As frequent critics of CentrePointe and its developers, we’re very encouraged by the new direction of the project.

But because the economic challenges to the project linger on, we’d like to see a more open, more flexible approach applied to the execution of the project as well. Perhaps the project could be built progressively or in stages, to allow for further construction as new financing becomes available. Perhaps it could be downsized to multiply financing options.

If – and this is a big ‘if’ – the developers can rethink their business model the way they’ve begun to rethink the design, the future of CentrePointe may be bright indeed.

UPDATE 6/6/2011: Graham Pohl now has a fine post up on an architect’s perspective of the new CentrePointe design and process over at ProgressLex.

The Trouble with Consultants

In the wake of the scandal surrounding Angelou Economics and their “recycled” economic development plan for Lexington, there have been a number of calls for developing a more homegrown economic development strategy.

These include Tom Eblen’s thoughts on local knowledge and leadership, John Cirigliano’s project-based approach, and our own ideas about extending the work of the mayoral transition teams.

In response to these calls for a more local economic development approach, I’ve noticed counter-memes emerging.

- One argument contends that we need consultants to fight insularity and to provide a valuable outside perspective.

- Another – in a particularly egregious defense of the indefensible – contends that this is what creative professionals do, and shame on those who called out Angelou – they destroyed a civic foundation of teamwork and trust.

I think these arguments are mostly wrong, and that they mostly distract us from taking the reins of our own economic development.

::

I’m pretty jaded when it comes to consultants.

I’ve managed a wide range of consultants throughout my career: industrial designers, research agencies, brand consultants, business strategy consultants, operations consultants, and even internet consultants at the height of the dot-com bubble.

I’ve engaged with enough consultants over the past 15 years to notice distinct patterns:

- Consultants play “follow the leader”. Every industrial design consultant starts by deconstructing what Apple does. Business strategy consultants start with Google. Or GE. Or Proctor and Gamble. They consistently take the leader in a category and dangle it in front of the client like red meat. The implication: “With us, you can make products like Apple. You can grow like Google. You can mint money like P&G. Just hire us and we’ll share that ‘secret sauce’.“

- Consultants tell clients what they want to hear. A few consultants throw some early jabs to get a client to sit up and listen – “Here’s why your marketing sucks…” Ultimately, though, they calibrate their recommendations to what they think the client wants to hear. What they deliver are bland, unobjectionable, safe ideas which don’t really threaten the status quo. “You can be wildly successful without discomfort!”

- Consultants position for the next engagement. The most successful consultants are always angling for their next big score. They deliver big, fat, visually-stunning reports loaded with aspirational recommendations which seem reasonable enough, but which neglect any significant detail on how to execute what they recommended. Because execution is something they would be glad to help you with, for an additional fee. They promise the ‘secret sauce’, but never actually provide the recipe.

- Consultants recycle. Relentlessly. Once a consultant comes up with a ‘big idea’, they don’t usually isolate it to a single client. They leverage that idea over and over again, across their business. They might customize or repackage their big idea for each client, or they might just make it a signature ‘product’ which they patent or trademark. About eighteen months after we rejected an industrial design, for example, we’d see elements of that design pop up in another client’s products. Many of the presentations and reports we got from consultants were 70% to 90% ‘boilerplate’ – stuff which could have been used for any of their clients in any industry.

Not every consultant follows these patterns, but enough do that these behaviors are fairly predictable. If consultants are so predictable, why do so many people work with them? There are a couple of unfortunate reasons.

First, consultants can provide a kind of political cover for difficult decisions: “I’m not recommending layoffs, the consultant is…” Their ‘independence’ and ‘objectivity’ make the consultants’ recommendations seem to carry more weight than when those same recommendations come from the people who hired them.

Second, and often related, is that consultants help us look busy when we’re tackling a difficult problem. They signal to others that we’re taking action: “Our consultant is looking into that.” In these cases, the appearance of action seems more important than the production of results.

Consultants can, indeed, provide a valuable outside perspective. Often, they’ve seen a lot of diverse examples of smart stuff that others are doing, and they bring those best practices to their clients.

But consulting engagements perform best when consultants augment and enrich the client’s work – when the clients have already done their homework; They fail when the client abdicates their work to the consultant.

::

Given my jaded perspective on consultants, I wasn’t too surprised when Ben Self exposed the Madlibs-style, fill-in-the-blank consulting work done by Angelou Economics in their “Advance Lexington” strategy for economic development.

Given my jaded perspective on consultants, I wasn’t too surprised when Ben Self exposed the Madlibs-style, fill-in-the-blank consulting work done by Angelou Economics in their “Advance Lexington” strategy for economic development.

Angelou fit a lot of the consultant patterns.

- They recycled reports they had created for other cities.

- They played “follow the leader”, holding out their work in successful cities like Austin and Boulder with the implicit promise that Lexington could be like them.

- They also told their clients what they wanted to hear – recommending a much more prominent role for report sponsor Commerce Lexington (which is partly subsidized by Lexington taxpayers) in Lexington’s economic development. That gives Commerce Lexington “cover” when it requests increased public funding; After all, it isn’t Commerce Lexington’s idea…

The problem for Lexington is that we attempted to have the consultant do our work for us without doing our own homework first. We can’t expect to get great economic results when we outsource our economic development strategy to others.

We had folks whose job it was to produce such a strategy. They just didn’t. They abdicated their responsibility to a consultant. And that’s not acceptable.

The important question: Why didn’t Lexington already have a strategy for economic development before we engaged Angelou?